In the real, physical world, extortion is a real problem and across the world, certain gangs and organisations see extortion as a legitimate way to earn real money, even apparently in the nuclear power industry! [10] The Internet is of course similar in many ways to the real world. If there are assets that are valuable to the owners, and if those assets are easily accessible and poorly protected, then online attackers are likely to take advantage of the situation, especially if the level of risk (i.e. probability and/or consequences of being held responsible) is low, and the likelihood of return (i.e. getting a ransom paid) is high. [1][2]

The Optus and Medibank debacles are the first time that large numbers of Australians have had first-hand, face to face experience with ransomware attacks and their consequences. These kinds of attacks have actually been taking place for many years, but Australia’s reporting laws are so weak when compared to laws in some US and European jurisdictions that many people (even those who have been unknowingly affected) are unaware of their occurrence.

This lack of awareness has led some organisations to believe that ransomware and extortion attacks are uncommon and that the perceived level of business risk does not warrant expenditure on improving cybersecurity maturity. Consequently many organisations are poorly protected and open to compromise, and are unable to even provide their customers with details regarding the information that has been lost or stolen when an attack does occur.

The first time I had anything to do with assisting with a ransomware attack must have been around eight years ago. The victim was an engineering company with a low level of cyber security maturity and as a result, all the company servers and backups were encrypted in the attack. Consequently, the victim organisation only really had two choices:

The engineering company was an otherwise strong and viable business, so option (1) was not actually a valid option, and that just left option (2).

This is backed up by studies [3] which show that the percentage of organisations that paid ransoms increased by approximately 5% over the past year.

Other studies clearly illustrate the kinds of situations in which a victim organisation is likely to pay the ransomware gangs. For example, the short paper, “Your Money or Your Business: Decision-Making Processes in Ransomware AttacksRansomware Attacks” [6] illustrates two scenarios:

So as the decision-making paper [6] explained, the likelihood of return for the attacker (i.e. the business will pay) is very high unless:

So why not pay the ransom? The line that is popular with Medibank and the government at the moment is that “you can’t trust the criminals to do what they say they will”. But is it really true?

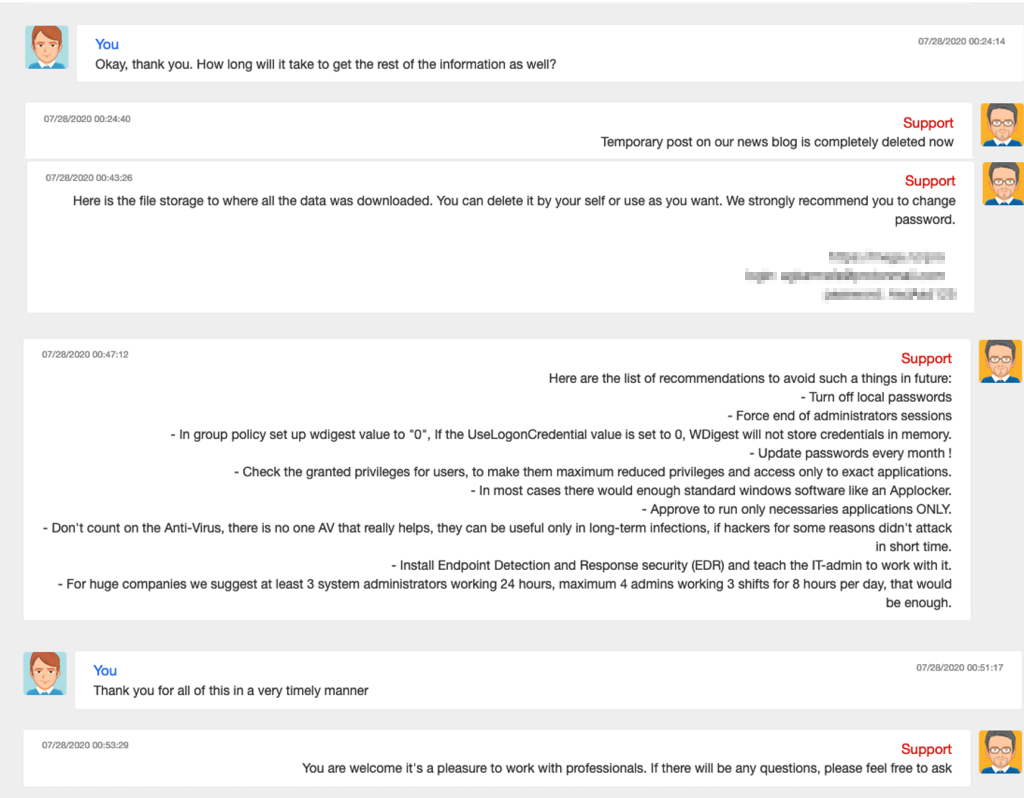

Studies [2][3] have shown that real ransomware gangs establish a reputation for punishing non-compliance and victims decide whether to pay or not to pay depending on how likely it is that they’ll be punished for non-compliance. In addition, it appears that the real ransomware gangs have also realised that victims are more likely to pay when compliance results in the recovery of lost data. In fact, once they have been paid, the gangs sometimes even provide assistance to help victims avoid a similar attack in the future.

Take for example the ransomware negotiations that took place when CWT (formerly Carlson Wagonlit Travel) was compromised a couple of years ago. The attackers originally demanded US$10M but as shown in a chatroom that was left accessible to the Internet, appeared to settle for less when CWT negotiated in good faith [8]. And once paid, the attackers then provided a summary of the vulnerabilities they exploited, and suggestions to help improve the level of cyber security maturity and prevent similar breaches from occurring in the future! Here is part of that chat…

This is backed up by the 2022 Cyberedge Cyberthreat Defence Report which reports that over the past two years the percentage of ransom payers who did recover their data rose to 72.2%.

And it also reflects upon my experience with the engineering company: The extortionist(s) provided help files in a range of languages and also provided assistance with bitcoin and funds transfer, and the engineering company was able to recover all their files.

So where does that leave us?

Well to start with, the attackers that are currently in the headlines are (under Australian law) criminals; yes, agreed, there is no question about that so we can move on, because that is not the point.

And yes, in some situations, criminals can be identified and brought before the courts, as shown in this case that was recently awarded to Google [7]. But that is not the point either.

We can even observe that in many cases, the extortion gangs are also sincere (illegal) business people, with sophisticated operating infrastructure, and a good understanding of reputation, consistency and customer service. But even that is not the point!

The point is this: Complaining about criminals doing criminal things after they’ve done their work is all backwards-looking and the-horse-has-bolted. That does not mean that I condone extortion in any way, shape or form; just the opposite! What it means is that we know that extortion can be extremely damaging or organisations and their customers, so it’s very important to look ahead before the gate is left open and note that organisations do not have to become victims. It’s not a fait accompli. That is the point!

As business owners, one of our jobs is to manage business risks, especially risks associated with business reputation and continuity. In theory, risks can be:

Sure, even after all that, an organisation might still be breached. In fact, if we go with the cheery advice of Robert S. Mueller, III, former Director of the FBI and Special Counsel into the Russian interference of the USA election: “There are only two types of companies: Those that have been hacked and those that will be hacked.” But Mueller’s advice was not given so that we could all just throw our hands up in the air and give ourselves over to abject, pre-ordained hopelessness like Marvin [9].

No, Meuller’s advice was given as a prescient warning. It’s time for organisations to manage risk and maintain a suitable level of cyber security maturity (here are some examples [11]) so that when an attack does come, there is a realistic expectation of timely detection, investigation, defence and recovery, without major consequences for more than a quarter of the country’s population.

Oh, and by “it’s time” remember that Mueller made his observation in 2012!

In conclusion, a meditative thought:

From dawn till dusk’s close,

Unwatched fruits tempt bandit’s touch,

In night’s silence, plucked

Give us a call and let’s chat about getting into the driver’s seat!

[1] “The Extortion Relationship: A Computational Analysis”

[2] “How Mafia Works: An Analysis of the Extortion Racket System”

[3] “2022 Cyberedge Cyberthreat Defence Report”.

[4] “A rare opportunity to see how negotiating with blackmailers looks like step by step”.

[5] “Cyber insurance. A risky business!”.

[6] “Your Money or Your Business: Decision-Making Processes in Ransomware Attacks”.

[7] “Google Wins Russian Botnet Hack Suit And Atty Sanctions”

[8] Ragnar Locker Targets CWT in Ransomware Attack

[9] The 1981 series was the better of the two!

[10] “Nuclear Power and the Mob: Extortion in Japan”

[11] Some examples of organisational maturity improvement in different industries